Gideon Bachmann in conversation with Tarkovsky

To Journey Within

This article is taken from the Swedish film journal Chaplin, no. 193,

September 1984 (a Tarkovsky special issue), where it appeared in a Swedish translation prepared by

Marianne Broddesson, entitled Att resa i sitt inre.

Chaplin is no longer in existence, but

Ms. Broddesson has kindly given Nostalghia.com her personal permission to post an English

translation of her article. So, the article was translated

from Swedish into English by Trond at Nostalghia.com. Interested readers

should also see the article Begegnung mit Andrej Tarkovskij by Gideon Bachmann,

in Filmkritik, Dez. 1962, pp. 548-552.

Gideon Bachmann first met Tarkovsky when Ivan's Childhood

was being screened and awarded at the Venice Film Festival in 1962.

He tape recorded their conversation for his weekly WBAI-NY radio film column.

Gideon Bachmann first met Tarkovsky when Ivan's Childhood

was being screened and awarded at the Venice Film Festival in 1962.

He tape recorded their conversation for his weekly WBAI-NY radio film column.

During the subsequent 20 years, Bachmann kept himself informed on

Tarkovsky's further work and often ran into him at various film

festivals. In 1982 they met again in Rome while Tarkovsky was

making preparations to shoot Nostalghia. Bachmann subsequently

had the opportunity to follow the actual shooting of the film.

The following interview is transcribed from taped material obtained

during the shooting of Nostalghia. As well, there are excerpts

from conversations that were never recorded, and a brief excerpt from

their first 1962 conversation, along with a few statements made by

Tarkovsky during press conferences in connection with the film's

production and some comments found in documentary material recorded

during the the shooting.

The continuity is from Bachmann's most recent recorded material.

Excerpts and quotes from other sources have been used when some

statement was in need of further clarification and explanation.

The questions have been somewhat re-written for cohesiveness.

GIDEON BACHMAN: First of all I would like to hear you talk about your

impressions from working in the West.

ANDREI TARKOVSKY: This is not only the first time I make a film abroad,

it is also the first time I work under foreign conditions.

I suppose it is difficult to make a film wherever you go

in the world, but I notice that the nature of the difficulties

vary a great deal from place to place.

Here, the greatest hindrance has turned out to be the constant lack

of money and time. Especially the lack of money hinders one's

creativity and the dearth of funds also results in a lack of time.

The longer I have to work on the film, the more costly it gets.

Here in the West, money rules. In the Soviet Union I never have to think

about what things cost. I just never have to worry about that. It is

indeed correct that the Italian TV Company, RAI, has been very generous

and invited me here to make this film, but the budget they have

allocated is obviously insufficient [Footnote: 1.2–1.5 Lire].

As I have no prior experience working abroad, some of this may just be

presumptions on my part. The current project is actually labeled a "cultural

initiative," and not a commercial venture.

On the other hand, it has been an extremely rewarding experience

to work alongside the Italian film team and their technical crew.

They are extremely professional and highly knowledgeable, and they

appear to be enjoying their work. Everybody appears to be loving

what they are doing.

But I don't want to make comparisons between our methods and theirs. It

is complicated and excruciating to make a film wherever you go, whatever

the reasons may be. What I consider most worthy of criticism here is

the total dependence upon purely economical factors, this has the potential

of jeopardizing the very future of cinema as an art form.

There has in the five films you have made during the last 20 years

— Ivan's Childhood, Andrei Rublov, Solaris, Mirror, and

Stalker — always been a strong conflict between the

individual and his surroundings. Is this the theme of Nostalghia as well?

It is always the conflict itself that is strong, not the individual.

On the contrary, the central characters are almost always weak persons

whose strength is born out of their weakness, out of the fact that

they just do not fit in, and are at odds with their surroundings.

Of course, there always exists a conflict between the individual and

the society, between distinctive individuals and their milieu.

That is, there always exists an opposition between these, and it

is this we refer to as conflict. Where there are no human relationships,

neither are there conflicts.

I am interested in working with characters whose relationship to society

is characterized by a strong element of conflict. They have an intense relationship

to the reality that surrounds them, and because of this they always seem to end

up in a conflict with their surroundings. I wish to follow that kind of person

so as to find out in what way they resolve their problems: will they cave

in, or will they remain true to themselves.

In a sense, one may say that this is the issue that is at the

very root of my dramaturgy.

Can you talk about how Nostalghia came into being?

I have been to Italy several times, and about three years ago

I decided to make a film together with a good friend, the Italian

author, poet, and scriptwriter Tonino Guerra. The film was to

revolve around my experiences in Italy.

I have been to Italy several times, and about three years ago

I decided to make a film together with a good friend, the Italian

author, poet, and scriptwriter Tonino Guerra. The film was to

revolve around my experiences in Italy.

Gortchakoff, who is played by Oleg Jankovskij, is a Russian intellectual

who comes to Italy on a business trip. The title of the film, for which

the word "nostalgia" is only a very insufficient translation, indicates

a pining for what is far from us, for worlds that cannot be united.

But it is also indicative of a longing for an inner home, some inner sense of

belonging.

The "action" of the film, the sequence of events themselves, was modified

several times, partly during the preparations while we were writing the

script, and also during the filming itself. I want to give expression to the

impossibility of living in a divided world, a world torn to pieces.

Gortchakoff is a Professor of History, an internationally known

expert of Italian architectural history. It is now the first time

ever he has had occasion to see and touch the monuments and buildings

which he heretofore only has known and taught on by using reproductions

and photographs. As soon as he comes to Italy he starts to realize

that one cannot communicate, transfer — not even learn to know — a work of art unless one is

an integral part of the culture from which the work of art has sprung.

So, he comes to Italy to trace the footsteps of a little known composer

from the 1700s, one who had originally been a Russian slave

sent to Italy by his Master to be educated as a court musician.

He studied at the Conservatory of Bologna under Giambattista Martini and

eventually became a renowned composer and thus subsequently lived in Italy as a free man.

An important scene in the film is when Gortchakoff shows his Italian

interpreter and companion, a young woman, a letter written by the

composer and sent to Russia, in which he expresses his homesickness,

his "nostalghia." Indications are that this man actually returned to

Russia, but that he turned alcoholic and subsequently committed suicide.

To Gortchakoff as well, the Italian experience turns out to be

life changing. The beauty of Italy, and her history, makes a great

impression upon his soul, and he suffers because he cannot internally reconcile

his own background with Italy. In spite of his experiences in Italy

initially only having a character of being purely external, he soon

realizes that when he returns to the Soviet Union it will involve

the end of something. This causes him to feel

depressed, as he knows that he will never be able to

forget or put behind him what he has experienced in Italy.

Knowing full well that he cannot make use of his Italian

experiences increases his internal pain, "nostalghia," which includes

an awareness of the fact that he is totally unable to share his

experiences with his dear ones at home, even with

those who were closest to him before he left for Italy.

This awareness of not being able to share with others his impressions

and experiences makes his stay quite painful. He is tormented, but at

the same time the need to find a soul mate is stirred within him, someone who

can understand him and share in his experiences.

The film is really a sort of treatise on the topic of

the nature of nostalghia, or about that experience which

may be referred to as nostalgia but contains so much more than

a longing. A Russian can only with the greatest of difficulty

part with new friends and acquaintances. His impending return to

the Soviet Union turns into a nightmare,

but this longing back to Italy is only one of many constituents

comprising this complex phenomenon referred to as "nostalghia."

What in the film expresses his seeking for a soul mate?

Gortchakoff abandons his original intention of writing a book about his

experiences and decides to rather pass on — or try to pass on —

the experiences he had in meeting an Italian, a teacher of mathematics from

a village in Toscana, played by Erland Josephson. For seven years this Italian has

prevented his wife and children from leaving the home in order to

save them from the disaster he fears the most: the end of the world.

This somewhat insane, mysterious fanatic becomes a sort of alter ego for Gortchakoff,

who recognizes in him his own feelings and doubts.

The teacher, Domenico, might be considered a positive influence in the

film, as his character personifies a necessary condition for the future. He becomes

Gortchakoff's main conversation partner and he represents an extreme case of the

spiritual unrest which Gortchakoff feels emerging within himself.

Domenico also stands for the constant search for the meaning of life,

a meaning to the concepts of freedom and insanity.

On the other hand, he is in possession of the receptiveness of

of a child and the extraordinary sensitivity often found in children.

But he has some additional characteristics which the Russian is lacking. Where the

latter is easily hurt and finds himself in a deep crisis of life, the somewhat

mad Italian is simple, no beating around the bush, and convinced that

he in his own enlightened outsidedness has found a solution to the general problem.

Tonino Guerra found this person in a newspaper clipping and

we since developed it a bit further. We have given him a touch

of a kind of childish generosity, which is strongly present with him.

His straightforwardness in relation to his surroundings

reminds one strongly of the kind of trust seen in a child.

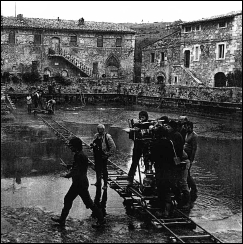

He is obsessed with the thought of of committing an act of faith,

such as walking straight across the pool — a gigantic, square, old

Roman bath in the center of the Tuscan village Bagno Vignoni — with a lit candle in his hand.

Gortchakoff attempts to do this, but Domenico, who considers that

an even greater sacrifice is required, goes to Rome and burns himself alive

on the Marcus Aurelius statue at the Capitoleum.

It is a violent sacrificial act, yet without any element of

fanaticism, performed with a calm faith in the salvation

to be revealed at the moment of revelation.

Do the main characters — the architecture professor

and the math teacher — have characteristics which

you can personally identify with?

Let us say that what I like the most in them is the confidence

with which the madman acts and the tenacity of the traveler

in his attempts at achieving a greater level of understanding.

That tenacity could also be called hope.

Does the relationship which unites these two people

reflect of your own feelings...?

My hero considers the "madman" to be a consistent

and strong personality, one who is certain of his

own actions, while he himself lacks this kind of confidence.

He is therefore utterly fascinated by Domenico, and in the end

it is he who ends up helping my hero to dare live without always

having to think and to rationalize everything. It is

in this sense — thanks to this development — that Domenico becomes

Gortchakoff's alter ego.

The strongest ones in life are always those who have

succeeded in retaining a child's confidence and intuitive

sense of safety.

Does there exist some sort of external reason for making this film,

some sort of obvious theme that provides us with the key to its internal tensions?

To me it is very important to again and again show

how crucial it is for people to be able to meet and

to function together. When one lives for oneself, in one's own

hidden away corner, there seems to rule a deceptive calm.

But as soon as two people come into contact with each other the

problem arises of how this contact can be made deeper and more profound.

This film is thus first and foremost about the inherent

conflict between two forms of civilization, two different

ways of living, two different ways of thinking.

Secondly, it is a film about the kinds of difficulties encountered

in human relationships.

When it comes to a love relationship between a man and a woman,

I wish to show how difficult it is to live together and feel an

affinity towards one another when one knows so little about the

other. It is easy to become acquainted on the surface, but much

harder to really get to know each other. Gortchakoff is in the

company of a female Italian interpreter, Eugenia, who is played

by the young actress Domiziana Giordano. It is also — put

in a simple way — an unconsummated love story between the

professor and the woman.

But seen from a wider perspective, the film will show the

impossibility of importing and exporting culture. We in the Soviet Union

pretend that we understand Dante and Petrarca, but this is not true.

And Italians pretend to know Pushkin, but that is also and erroneous assumption.

Provided there are no sweeping change, it will never be

possible to transfer a people's culture to a person who is

foreign to that culture.

Gortchakoff's suffering begins when he realizes that he sooner or later

has to stop being absorbed by all the new that surrounds him — emotions and

people which have caught his attention during his stay in Italy. New

fascinations and interests have begun to stir within him. He meets a person,

who, just as himself, understands that real relationships are impossible,

and who therefore sacrifices himself. He, Domenico, suffers from the same

kind of internal fragmentation: that of not being able to unite the enitre

world within oneself, all that is good, people, emotions and spirit.

Everyone considers Domenico to me "mad," and perhaps he is. But the reason

why he is considered insane, and the resons for his reactions and feelings,

feelings which Gortchakoff recognizes very clearly, are absolutely normal.

Is it an encounter with Self in a different incarnation?

Gortchakoff recognizes the similarities, and in spite of the fact that their

encounter is relatively brief he can sense the connection between them. It is

the similarity of their suffering that unites them.

During the shooting of the film, Domenico became even more

important and we have given his character a much firmer shape.

He expresses even more clearly Gortchakoff's increasing awareness

of the impossibility of real contact. To a certain extent he

also gives expression to the fear which we are all forced to live

in, our uncertainties when it comes the the future. It is

fear that is the problem in the psychological state in

which we are — in our waiting for the future and what it holds.

Everybody are worried, not at rest, about the future, and this film is very much about

this our unrest. It is also about our apathy, which causes us to allow things to

develop any which way. We are worried, but at the same time we do nothing to change the situation.

Granted, we actually do a whole lot, but what we do do is hopelessly

insufficient. We should do more.

As far as I am concerned, all I can do is this film. It is what

little I have to offer: to show that Domenico's struggle concerns us all, and to show that he is

absolutely correct when he accuses us of being too passive. He is "the fool" who

accuses "the normal" of being too lazy, and sacrifices himself so as to shake up

his surroundings, thusly underlining his own warning. This is his sacrifice and it is

all he can do. His intention is to force us to act, to change the "now."

Do you share the world view which causes Domenico to commit this act?

The essential element of Domenico's character is not his

world view per se, that world view which leads him to commit

the ultimate sacrificial act, but rather the way in which he

chooses to resolve his internal conflict. Thus, I am not as

interested in his starting point as I am in his emerging

conflict. I want to understand and try to show how

his protest was born and the way in which he expresses it.

I am actually not as interested in how he expresses it; the most

important thing is the very existence of the protest itself. I consider

any way in which a person choses to express a protest to be significant. Even

a simple opinion that is expressed clearly and without fear (an opinion

for which one may very well be considered insane) can mean more, and be

more significant, than the talk of the so-called "normal," who

are given to idle chatter and never actually do anything.

Is it important for you to reach a large audience with your

ideas?

I don't believe that there exists any form of art film that can

be understood by everyone. Consequently, it is almost impossible to make

a film that works for everyone watching it, and if it did it

wouldn't be a work of art at all. Irregardless, a work of

Art is never accepted without objections.

A director like Spielberg has an enormous audience and earns enormous

sums and everybody is happy about that, but he is no artist and

his films are not art. If I made films like him — and I don't believe I can —

I would die from sheer terror. Art is as a mountain: there is a peak

and surrounding it there are foothills. What exists at the summit

cannot by definition be understood by everyone.

I don't believe that it is my task to capture the audience, to make

them interested in what I am doing. Because that would imply that I was

underestimating their intelligence. After all, I

don't believe that the audience consists of idiots.... But

I often do reflect over the fact that no producer in the world

would dare invest 15 kopek if all I promised him was to make a work of art.

Therefore, I invest all my energy and diligence into every film I make.

I try to do my best, otherwise I may never get the chance to make a film again.

I think that I, in my own way, have succeeded in getting the attention of

the viewer without having compromised my own ideals. And that is, after all,

what counts. I am not some intellectual type drifting up in the blue yonder, and

I am most definitely not from some different planet. On the contrary, I feel

close ties with the earth and its people. Briefly put,

I don't want to seem more nor less intelligent than what I actually am.

I stand on the same level as the spectator, but I have a different

function. My mission is different from the viewer's.

It is not essential for me to be understood by everyone.

The most important to me is not to be understood by everyone.

If film is an artform — and I think we can agree that it is — one must

not forget that artistic masterpieces are not consumer goods, but rather

artistic pinnacles expressing the ideals of an epoch, both from the

viewpoint of creativity and with respect to the culture from which it springs.

A masterpiece gives form to the ideals of the particular epoch in which we live.

Ideals can never be made immediately accessible to everyone.

To be able to approach them, one must grow and develop spiritually.

If the dialectical tension between the spiritual level

of the masses and the ideals to which the artist bears

witness disappears, it would simply mean that art had completely lost its

purpose and function.

Unfortunately, one can rarely say that the films one see exceed the

level of mere entertainment. The fact that I treasure Dovsjekos's, Olmi's,

and Bresson's films is due to that fact that I am attracted by their

pure, simple ascetic touch. Art must strive to achieve these characteristics.

And trust.

The prerequisite for a creative idea to reach the consciousness of the

viewer is that that creator harbors a confidence in the viewer.

They must be able to communicate with each other at some common level.

There is no other way.

Is is completely worthless to try to violently force onto the viewer some understanding

even when it concerns something that is entirely obvious to the originator.

But even if one must respect the viewer's ethical principles, one must

not allow oneself to compromise one's duty to create a modern form of film art.

One must never allow oneself to be swayed by the regressive tastes of the audiences.

I don't believe in the literary theatrical dramatical construction. It has

nothing in common with the dramaturgy that is particular to cinema as art form.

Most modern films serve no other purpose than to explain to the viewers the circumstances

surrounding the action, the narrative of the film. But in film one does not need

to explain, but rather to directly affect emotions. The heightened state of emotions

then naturally lead the intellect forward.

I am trying to arrive at a principle of editing the film that will

permit me to communicate the subjective logic — the thought,

the dream, the memory — instead of the subject's own logic.

I am looking for a form which springs out of the actual

situation and the human condition of soul, i.e., the

factors that influence human behavior. That is the first

condition for presenting psychological truth.

Is "the logic of the subject" the same as the plot of the film?

In my films, the story itself is never particularly important. The real

significance in my works have never been expressed through the

plot of the films. I attempt to speak about what is significant,

but without unnecessary distractions. By showing certain

things that are not necessarily joined at the purely logical level.

It is the stirring of thoughts within that conjoins them for us, in the

inner man.

Would you say, then, that what is important to you

is the emotions that you communicate in your films,

and not the stories being told themselves?

I am often asked what this or that means in my films.

It's terrible! An artist does not have to answer for

his purposes. I do not harbor any particularly

deep or profound thoughts about my own work. I simply have no idea

what my symbols represent. The only thing I am after is

for them to give birth to certain emotions. Whatever feelings

emerge based on your response from within.

One always tries to discover concealed meaning

in my work. But wouldn't it be strange to make a film

and at the same time try to hide one's thoughts? My images mean nothing

beyond what they are.... We don't know ourselves very well; sometimes

we just give expression to forces that cannot be measured

in conventional ways.

In your films you have often used "the traveler"

as a metaphor, but never before in such a clearly defined

theme as in Nostalghia. Do you consider yourself

a traveler?

Only one journey is possible: the journey within.

We don't learn a whole lot from dashing about

on the surface of the Earth. Neither do I believe that one

travels so as to eventually return. Man can never reach back to the

point of origin, because he has changed in the process.

And of course we cannot escape from ourselves; what we

are we carry with us. We carry with us the dwelling place of our soul, like

the turtle carries its shell. A journey through all the countries of

the world would be a mere symbolic journey. Whatever place one arrives

at, it is still one's own soul that one is searching for.

In order to conduct the search for ones own soul

one must have a strong confidence in oneself. But

today I think it seems as if Man's belief in his own

capacity to take a stand has given way — everywhere — to

a fanaticism which rather values the belief in external events, ideas which

come from the outside.

Yes, I have the sense that mankind

has stopped believing in itself. That is

to say, not "humankind" per se — that

concept does not exist — but rather

every single human individually. When I

consider contemporary man I see her as a choir singer,

who opens and closes her mouth in synch with the

rhythm of the music, but without uttering a

note. After all, everybody else is singing!

She just pretends to be singing

along as she is convinced that the others'

singing is sufficient. She behaves like

this because she has lost faith in the significance of

her own personal actions.

Contemporary man is without faith, completely

without hope that he might be able to influence

the society he or she lives in through his or her own

behavior.

What is the point of making a film in such a world?

The only meaning of life lies in the effort that is

demanded in growing spiritually, to

change and develop into something different than

what we were at birth. If we during the span of

time between birth and death can achieve this, in

spite of the fact that it is difficult and that

progress may seem slow at times, then we have

indeed served humanity.

I am increasingly becoming interested in Eastern philosophy

wherein the meaning of life lies in contemplation

and Man's being an inseparable part of the Universe.

The Western world is far too rational and the Western idea of

life appears rooted in a more pragmatic principle:

a little bit of everything in a perfect balance, so

as to keep the body alive and merely "exist" for as long as possible.

Do you not believe in the concept of time

as a gauge for the purpose of depicting the experience

of existence?

I am convinced that "time" in itself is no objective category,

as "time" cannot exist apart from man's perception of it.

Certain scientific discoveries tend to draw the same conclusion.

We do not live in the "now." The "now" is

so transient, as close to zero as you can get without it being zero, that we

simply have no way of grasping it. The moment in time we

call "now" immediately becomes the "past," and what we

call the "future" becomes the "now" and then it immediately

becomes "past." The only way to experience the

now is if we let ourselves fall into the abyss which exists between the

now and the future.

And this is the reason "nostalghia" is not the same as mere sorrow

over past time.

Nostalghia is a feeling of intense sadness over the period that

went missing at a time when we forsook counting on our internal gifts,

to properly arrange and utilize them,... and thus neglected to do our duty.

|