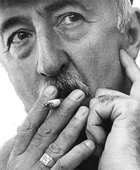

Mikhail Lemkhin"There is no Return to Anywhere"The following is an interview with Otar Ioseliani conducted by Mikhail Lemkhin in San Francisco in 1991. The interview was first published in New York by the Russian daily newspaper Novoie Russkoe Slovo, on September 11, 1993. It has been translated from Russian into English by Nathan Lemkhin, and is reproduced by Nostalghia.com with the kind permission of Mikhail Lemkhin. Photo: © Mikhail Lemkhin / lemkhin.com.

The name of the film is Chasing Butterflies. It is a bitter film; I suspect it will be the last one in a series of Ioseliani films that began with Favorites of the Moon. According to Ioseliani, the destruction of traditional ways of life, of cultural legacy and continuity, entails the destruction of culture. This destruction begins with culture's material embodiments, from household utensils and dining sets to art, together with its mission of passing down spiritual information to future generations. Deprived of that spiritual connection, of the spiritual experience accumulated by their ancestors, people live as though in a vacuum, without a moral frame of reference. That was the theme of Ioseliani's first Western film, Favorites of the Moon. Life goes on, however, and Ioseliani sadly examines these new people — comical and aggressive, cruel and pathetic — making an honest attempt to understand how hopeless their situation may be.

Andrei Tarkovsky, being a maximalist, agonized over the same problem:

In Nostalgia, Domenico sets himself ablaze, convinced that people's

link to Culture and God is lost forever, and Gorchakov dies while

trying to deliver a candle that he is carrying, to protect and

preserve the living flame, which can be extinguished not only by the

wind but even by his own breath; the flame links Gorchakov both to

Domenico and to Gorchakov's own ancestors — to his roots:

Ioseliani's next film is also set in a small village. The name of the film is Let There Be Light. The film is about the creation of a world. The new world's creation turns out to be the destruction of the cultural ethos of a tiny African village and a total deindividualization of its inhabitants. The established life of these amiable and naive people is eliminated by the coming 'civilization', by an impersonal alternative order of things, rather than someone's hostility or benevolence. A truck passes by, followed by another one; farther in the distance, machines roar, woods are being cut; and then — a whole culture ceases to exist. Gone are the miracles, animal hunts, and healing herbs; the sorcery and shamanism; the fairy tales and stories; the rules according to which their fathers and grandparents lived; and the notions of what is beautiful and what is ugly, what is right and what is shameful and dishonest. Gone is the village itself, never to exist again. Not long after Otar Ioseliani made his African film, I taped a conversation that we had about the film, as well as about cinema in general, and about that which shall never exist again. For certain reasons, I did not publish it at that time, but now, after listening to the tape, I see that Otar provides explain much of what will help his viewers understand his films — both his old films and the ones made after the conversation took place.

Mikhail Lemkhin: Otar, you have made your last three films in three different countries — Favorites of the Moon in France, A Little Monastery in Tuscany in Italy, and Let There Be Light in Senegal. You know, what's surprising to me is that, in spite of the fact that you choose to work with such culturally diverse material, your view does not seem like a foreigner's or an outsider's view. And yet, these are all still unmistakably "Ioseliani films." Otar Ioseliani: It is the social fabric or the cultural milieu that can change, but no changes occur in our criteria, our notions and systems of values. It is known that our personalities get determined by the age of six. And by eighteen or twenty, each of us is already a fully shaped person with a hierarchy of values which is intrinsic to him and which, apparently, will not change any more; although modifications will be made in it depending on the experience that one is destined to acquire. And if I was born in Tbilisi, in a particular environment, with particular parents, and was molded by a particular cultural stew — all of that can't be changed. But that a film made in France comes out as though it were made by a Frenchman — that has to do with something else, I think. What you're filming, if you're attentive, will itself suggest how it should be filmed, and then the very environment will enter the screen, with all the dimensions of truth which it brings to your narrative. But I don't think that a Frenchman could make a film like Favorites of the Moon; and I don't think that an Italian could make a film like A Little Monastery in Tuscany, and I don't think that the film that I made in Africa could have been made by an African director. Out of the question. Because that key that you use to open this or that page that the world presents to you — it always stays the same, and the secret of your vision — it dies with you. The whole set of standards, likes, and dislikes which you attach to this or that context, that whole conglomeration — this was all shaped a long time ago and is a part of your ego. In that sense, it makes no difference whether you're filming in Africa or in Italy. Your view is always with you. The sense of a lack of ease is due to from something different, namely the fact that you are unfortunately forced to film the life of other people [other than your own], on the other side of the world. [ What you're filming, if you're attentive, will itself suggest how it should be filmed, and then the very environment will enter the screen, with all the dimensions of truth which it brings to your narrative. ] ML: Otar, it's both like that and it isn't: Of course, each person always carries such a key with them. The problem is that not every key fits the life of a foreign country. Your key turned out to be universal, you see? Plus — and this may be the main thing — you have an interest for that foreign life. We know many people among the émigrés, dozens or hundreds of them, whose key does not fit here — it does not open anything, doesn't reveal anything. And sometimes they don't even try to do it, they have no interest. But you may lose whatever interest you've got left, too, if you try it once, then twice, but the key that opened things back home will not open anything here. OI: I think that it has to do with upbringing, Misha. If one remembers people who traveled a lot, who lived in different countries, they're usually people who considered the whole world to be worthy of attention and respect; they were ready to learn and absorb new things. That would be, say, Lawrence of Arabia... Or Pushkin, who was always avid for more knowledge, always dreamed of traveling. With his upbringing, his type of personality, he would have enjoyed living in Italy or in France. Or Herzen, for instance. He felt great abroad, in spite of ringing that Bell [3] of his so indefatigably. But then there are people who isolate themselves. Having left a country, they try to recreate it in a different place. They flock together and cling to each other. It is particularly clear in the case of our emigration wave. The older wave, given their culture and the configuration of their brains, have perfectly blended into the French milieu. While in our emigration, there is a large number of people who perceive the world as an alien place and even fear it. There are people who have lived abroad for ten years, and still don't know any language but Russian, which is very sad. ML: Otar, to what extent do you think your films are Italian, African, French, and to what extent are they Georgian films? To put it another way, to what extent do the problems which you speak of reflect the problems of Georgia? OI: My films are parables, after all, and the language of a parable is — geared toward a certain kind of universality. Like my African film — that could have been shot in Georgia. But it wouldn't have been a pure experiment for a whole list of reasons... ML: Which have to do with organization and censorship? OI: No, no, no. The lab experiment would not be pure. That is, I would be able to hear all kinds of regional feedback noises, and they would interfere with the clarity of my diction... ML: You're saying that these noises would distract you because, as they would be intelligible to you, you'd attempt to make sense of them, and thus, perhaps without realizing it, would modify your conception? OI: Yes, yes. And also, nothing occurs in Georgia in the pure form that it takes in my African village; rather with overtones which obscure the lucidity the narrative. A film about the deterioration of culture, of cultural values and traditions, let's say, the destruction of ideal ethos, could obviously have been made anywhere. But it seemed to me that it was precisely there, in Africa, that I would be able to make a film in a pure genre, in the language of a parable. But that's me. An African lives in that world, and that is why it would be impossible for him to reach that parabolic lucidity given that material: It would be obscured by his knowledge of things. He would not be able, for instance, to give a general idea of tradition, right? In every place he would look for specific ethnographic traits, the exact rituals and rites which mark that particular group or tribe. If I decided to stay true to the ethnography of the place where I was filming, it would hinder me: I would not be free, I would be constantly corrected by the locals who would tell me: "This is the way it's done, and not that way". Then the film would slip through my fingers. Therefore, I purposely invented all the minor traditional and ritualistic details, but had to do it in such a way that the locals perceived them as believable. So that they played some people from some country who do things that [way] and believed that this could happen. ML: You invented the rules of the game, but it was they who played it, right? But you had to find people who could play your game naturally. OI: Exactly. I came to Africa with the idea that such people should exist somewhere. And if I hadn't been lucky, I would not have made that film. My vision came from the literature that I have had the chance to read, or, rather, from the essays written by the missionaries. But since the demolition had already gone pretty far, it was very hard to find a group of people who naturally existed within the framework of their culture. What they play in the movie could not have been acted — this is the way they really are. They are cheerful, lively, not malicious, indisposed to lying or thievery. They believe in the sacred forest, in the power of spirits... And the relations between them are founded on full respect for each other, for children (since children are destined to become adults and travel the whole path), for the old. Only thirty to forty years ago, one could find something comparable in Georgia, but not today. Culture, in the sense of a well-constructed system of human relations, has collapsed there. Maybe it was one of the last countries. But everything's collapsed, practically, with the departure of the previous generation. Now, all conversations on the subject pertain to nothing but history. ML: So, while filming in Africa, you were thinking of Georgia? OI: I filmed a fairy tale, or a parable, or a fable. And what those people did had to fit their notions, correspond to their very interior, if one can put it that way. One could not act unethically toward the very structure of their life. They took part in my tale without its purpose or contents, but each part had to be acceptable to them. You could not offend their feelings or force them to do what they were not used to doing. They were themselves. ML: By the way, how do you usually work? Do you show the screenplay to your actors? OI: I try not let the actors read the screenplay. Having read the screenplay, they usually see an angle to their role that I have no need for. ML: You know Tarkovsky worked that way as well? He suggested that actors act only today's scene, react to the current situation. He talked of how some of them resorted to various tricks to find out something on top of today's role. For instance, Terekhova, when she was cast in The Mirror. OI: Oh yeah, that's terrible! That's the Stanislavsky Method — to become embedded in the characters life... That's dreadful! If you are making a movie, you should know what it is that you want it to be about. The more the actor knows, the more he interferes with the director, because he already acts out that resulting idea, that knowledge of his character. ML: Sorry, I distracted you from the subject of your film. OI: I'll say one more thing: It is very important to believe that you're addressing your message to someone who will understand it. There's never a certainty that the viewers will necessarily understand what you are saying to them, and yet you need to assume respect for them. Maybe they'll have a different understanding of it; however, each one will carry away a part of your attitude towards the phenomenon of life. While such hope still exists among us, we can work. If only one person sighs with you, then the work is worth it. But as soon as that situation disappears — and that may happen in the very near future — it's gonna be hard to make films just to make films. There is an erroneous Soviet notion that art can be used to shape people or set them on some track. Nonsense. It's just that there's a circle of people who think the same way we do, and when I read a book and find that I like it, why, I like it because these are my feelings, only what a great, what a fantastic way the author has found to phrase them! ML: Sometimes, it seems like you hadn't thought or felt that way, but you find out that you did. Only you didn't verbalize these thoughts and feelings you had. OI: Yes, yes, you didn't think them through in words... And so, while such type of contact is possible, it is worth doing one's work. It's even worth working in a way that makes life difficult. ML: You know, sociologists say that you can make contact with those within your circle and those just a little away. That refers to any kind of contact — whether it's through art or politics. Your circle and just a little further, and beyond there it's a different language. Mixed notions on marginal territory can still exist, there language can borrow concepts from both sides. But one more step — and everything changes. OI: Of course, it comes down to linguistics — if we are not speaking the same language, then how is it possible for us to understand each other. If by language one means a set of experiences. Indeed, we orient ourselves towards people who have a set of standards and criteria similar to ours, and it's exactly these people that appreciate our work. Placed outside that circle, the work loses the meaning that the author inserted in it. And, for all we know, it could be that the versions of Homer's epics that have come down to us were banal, repulsive, dishonest, distorted the truth, and destroyed standards, and as a result weren't acceptable to the people of his time. That could be, I say. But as time passed, the same text entered a different sphere, and we gave it a different meaning. ML: And it could even be that the text itself has influenced the formation of later esthetic and historical notions. OI: Could be. Possibly. It was already in existence as one of life's phenomena that people interacted with... In any case, I think that the text, having fallen out of the milieu where it could be read correctly, and that is why I insist that the language of the fable is most universal. Each person can attach his experience to a fable. ML: Your African film comes maximally close to a fable. Do you believe that it will be understood by local audiences in an adequate fashion? OI: In a different way by everyone, of course: It'll be understood in a certain way in Europe, and in a completely different way in America; differently by blacks and differently by whites. For the Georgians, it will be a film about Georgia; for the Russians, a film about the destruction of the Russian village. And Europeans will think: What have we done in Africa with our colonization! ML: However, each work contains a seed, an initial impulse which generally does not lie on its surface and is hard to define verbally, but that impulse is the very embryo from which a film or a book develops. In essence, it's that thing that makes you languish. A person who has not made art his vocation will say: "I've got the blues today," or snap his fingers, or attempt to rescue himself with the aid of some metaphor that is familiar within his circle; or compare himself with a book or movie character. While an artist will begin telling it and end up with a book or a film. And so, do you think that your train of thought or emotion could be understood by a Frenchman, an American, and whoever else? Or do you suppose that only a Georgian can understand it in an adequate fashion? OI: Yes, apparently, yes. If one goes back to the very start of the associative chain — then yes, a Georgian. But if the film becomes subject to extrapolation, let's put it that way, the means that it has touched upon something common for both Georgians and people of a different nationality and culture. You know, sometimes people ask: "How did you invent it all?" One cannot invent anything, I'm firmly certain of that. One can just get lost in thoughts about something, and the solution will suddenly come to you; or one can experience something very intensely, and the universality and discrepancy of the feeling will yield some sort of formula. ML: So, given any degree of universality of this or that method, given the maximal creative honesty, your most intimate viewer would be the one who was shaped by the same "cultural stew," as you say. All things being equal, would you want to make your next film in Georgia? OI: To make a film in Georgia would be very painful for me at this time. A whole world has collapsed there. And people appeared there who have no memory of kinship. People who have no memory of their past, no knowledge of it. The viruses of mercantilism and egotism have enter that environment, which has never known anything like it before. It would be very painful for me to film in Georgia, because that is that the film would have to be about. And that process would not be an easy one. But you know, that is, after all, a reproach. And to reproach is not a grateful thing to do. And the main thing is that you cannot achieve anything with reproach as your tool. That's a hopeless affair. The process would be painful. Some very hard thinking is needed here. Frankly, I don't even know how to do it all. To talk of what you know but use different material — that's a kind of a pretext. Bit by bit, ones baggage gets used up... I left Georgia due to circumstances that were beyond my control. I hadn't filmed anything in eight years and was granted permission to leave from high up the ladder. The bureaucrats hoped that I would never return and that they were rid of me, thank God. ML: Did you feel that you were leaving for good? OI: No. I was just leaving to work. ML: There was no thought that going to the airport was like going to the graveyard? I had a feeling that I was being taken to a graveyard, and I'm seeing it all for the last time, until the minute they'll close the casket and cover the hole. OI: Because you were really leaving. If I had to leave forever, why, my films would have been different. For my addressees remained back there. I made the film Favorites of the Moon for them, so that they'd scratch and think. But one uses up one's reserves. Or else, one needs to start really living in a different country with a set of problems and associations which pertain to that country, but that's something altogether different. And at this age, I'm certain, it's impossible to do. And the problems of a foreign country can never become truly intimately yours. They can become yours only insofar as you can see their universality. But for you they will never have the same concreteness as they do for a real human community of people that are born and raised within that community. However, when I return to Georgia, I find myself in yet another foreign country. There is no return to anywhere period. People die, and a generation vanishes, together with the whole frame of reference that we use for support, and the sense of ease disappears. As if everyone keeps drawing toward some barrier where all fall down and what comes in turn are new waters. Heraclitus was right, of course: you can never step into the same river twice. ML: A few days ago, I and Agniezska Holland, a Parisian who left Poland, were explaining our emotions simultaneously to this American fellow. He was saying: "Well, now times have changed and one can go back there"; while we were trying to make him understand that there was no place for us to go back to. You cannot go back to the past. OI: It became the past. All things are different now. There is no sense in attempting to go back to childhood sites. Childhood is gone, and you won't get much out of that but pain and disappointment. So you grow sad. But one must go back anyway, because what remains is some understanding of people's inner motions. And language plays a very important role, for only we speak it and know it, and it contains that associative stock as well as our system of values. ML: You know, Brodsky said that when he arrived here, he made a resolution: The world expects moans and complaints from you, hence it would be bad tone to actually moan and complain. And he kept himself in check and tried not to permit himself to do anything of the sort. And then, said he, "The mask grew onto the snout and became a face." And now, he said, one need not make any effort... OI: He said that? Good for him! ML: But at the same time, he continued to say words like: "Back home, I used to do it that way" or "Back home, I wouldn't keep in contact with that kind of person." OI: Home means "the way it used to be," let's say it that way... How did I leave? I had a conflict with The Center, as they call it now, the State Cinema, the official propaganda machine. They rejected all the screenplays, whatever I brought in. And I could not make concessions. That's why they were pleased to let me go. It was burdensome for them as well — to have me not working and everyone asking them: "Why isn't he working?" They didn't know how to respond. "He's thinking," they would say. Well, OK — for a year. You cannot just think for a whole eight years... I think it isn't bad that I didn't work for 8 years: to work all the time is dangerous as well. ML: It only seems so now. OI: One can't work without breaks. You stop living. ML: You didn't work without breaks. Before Pastoral, there were pauses between your films as well. OI: There were. And they were somehow natural, I think. I could never, say, finish one film today and sit down at my desk tomorrow and start thinking of another one. Nothing will come of it. It's the film that will invent itself, plant itself in my head, and tell me what it wants to become... Such is our profession. You know, I don't consider as my colleagues those who adopt big literary texts for the screen. That's a different profession. Not even to mention those who film truly great works of literature — that's simply absurd. It's a pretty bad idea, for example, to mess with Mikhail Afanasievich Bulgakov. Everything that he wanted to say to the world he communicated with the means that were natural to him. And he's not subject to explications. That's what I think. If it's some lousy little book, then I guess you could do it. But then why use the book? You can invent it yourself. Big deal, as if it were Newton's Law. ML: Well the book's significance could be that it turned out to be that very initial impulse that turned on your emotional apparatus. After all, the story by Bogomolov called Ivan is so far from Ivan's Childhood that there's almost no connection left. OI: Could be, could be. I don't like that method. Why screen Dostoevsky? One has to read Dostoevsky. They ask you: "Did you see War and Peace?" "Sweetie," I say, "you've got to read War and Peace!" What the hell do I need for it to have — who was it, Ktorov? Playing old Balkonsky? Why should Pierre be played by Bondarchuk? What is all that for? It stays in your head. Imagine, people who have not read the book will watch the movie, then start reading and they'll see Bondarchuk. Why, what kind of thing is that? When, my father saw the movie — he had just returned from exile then — they asked him: "Well, what do you think?" And he said: "All of the nobles move like liveried servants." So that's all lost and one cannot be taught how to do it anymore. ML: One doesn't want to believe that some things don't exist anymore. OI: The fact that some things don't exist anymore is sad only for the last of the Mohicans. The following generation won't be either sad or glad about it. ML: General reasoning is one thing, Otar, but it's another thing to end up as one of these extinct reptiles, the last of the Mohicans. The future is made by you, but not for you. Remember how it goes in that story by the Strugatskis? I don't know if you like them or not. OI: Yes, very much. ML: You work for that future — it is your vector, your aspiration. And, all of a sudden, you turn out to be a witness, a contemporary of, a participant in this demolition. Here it is, the new world, but you aren't needed in it any more, and you yourself have no real human need for it. These are new conditions to which your organism and your consciousness aren't adapted. Remember the Strugatsky story: The mocretzy stop existing physically, but from them, from their flesh, a new world originates. But Victor Banev, whose flesh has stayed intact, cannot and doesn't want to merge with that world [4]. OI: In any case, all the moans and tears about how everything was good before and how worse times are coming stem from the fact that what came earlier was familiar to us, and that this familiarity has gone, never to return. Thats how it is in this world. What's coming will be a different time, just as shitty as ours, but special and intelligible to someone else other than ourselves. ML: Another question. What did we imagine the future to be? So much for whether we're needed there or not. But how did we picture it? The things that are happening now in Georgia — is that the future that you imagined? OI: Unfortunately not. Unfortunately not. I had a friend who got a plot of land for a summerhouse. It was near Moscow. So he was inspecting the land with a forest warden and saw that it had nothing growing on it but aspen trees. So he says to the warden: "Why is the land so bad here — nothing but aspens." And the warden said: "There was a thick forest here before, but they cut it, and now it's only aspens. But you know, he says, see that firtree growing and over there is a little oak that made it. If you wait 20–30 years, it will be forest again and the aspens will disappear. But if you level it twice, then only aspens will grow from then on." And Georgia was leveled at least four times within a brief historical period. It was leveled during the invasion of the 11th Russian Army at the time of the first emigration wave; leveled during the large peasant uprising against the Soviets in 1924; Stalin has purged it of even those communists who still believed in something, and, has naturally wiped out all the aristocrats. Then, there was a war, where 600,000 people were killed, and Georgia's population at the time was 2.5 million. Well, this sufficed. My dad had 11 brothers, and I am their sole heir. You can thus imagine what happened. And my mother and my aunt who raised me did so in spite of the existing circumstances. I was lucky. For later on, if you assume the responsibility of being an artist, it's very significant where and how you were brought up. If you grew up in a foster home, if you were punished and whipped and your teachers were mean; or if you grew up in the house of a drunken father who thrashed your mother, beat his kids and broke furniture, while your mother was also cruel and drunk, then your films or your books would be very different from those you would make if you had grown up in an environment of attention, love, respect, and care. Georgia's been leveled four times, so no matter how much we, the remaining Georgians of a different epoch that are left by accident to live out the rest of our days, no matter how we try or wave our arms in the air, it all cannot be restored anymore. True, there are texts, the texts that have had a certain influence on those young people who gathered on the square and were mercilessly beaten and chased away. There are texts, and maybe they deliver some sort of structure. Texts have to be read, and for that you need teachers. There were songs which required skill, not to mention ability. They stopped singing the songs, stopped teaching them and stopped learning them. The whole wave that has appeared with walkmen and videocassettes has finished off the last remainders. A whole culture has collapsed; since culture is not something where one cellist performs, and the others, who don't know how to play, listen to him. Culture is when everyone knows how to do something. ML: Naturally, when Liszt visited Russia and played at home salons, the people who played the piano themselves were in a position to appreciate his performance; he just played better than they did. OI: And yet it seems to me that there is still some sort of energy in Georgia that can lead it to rescue. I wait in hope that it will happen.

Two years passed, and Otar Ioseliani brought yet another new film to San Francisco. A small town in France. People who have lived side by side for many years. Who all know each other, meet in church, and play in an amateur brass band; bicycle to the shop, buy baguettes, catch fish, hang laundry, wake up with a hangover. We don't know anything about an old woman who dies in her chateau; how, when and why she got there is not important. She has a sister in Moscow, and the sister, an old lady like her self, comes to the funeral with her daughter. Other relatives come as well, a huge family gathers together. The funeral over, everyone takes a seat in the living room. The will is read, and, to everyone's disappointment, the sister from Moscow inherits the chateau. The snappy daughter of the new owner immediately sells the chateau to Japanese businessmen. What would she do in this village? She moves to the city — Paris? — to an apartment where mother's quarters are arranged behind a partition, and the rest of the place is a gathering for what could be the former Moscow crowd: festive meals, drunken conversation, guitar music, quarrels (by the way, one of the guests sitting at the Moscow-in-France-style table is Alexander Askoldov, a Muscovite now living in Berlin); she has transported the Moscow life to Paris with the only difference that here she can go to the store and buy a bunch of dresses, hats and fur coats, and issue an order to her mother: "I prohibit you to do the dishes. That's not acceptable here. There are servants." In the meantime, the new owners move into the old chateau. These new owners try to resemble the former, real hosts in all aspects: having purchased the estate for 1.5 million dollars, they bicycle to the bakery for the same baguettes, buy vegetables at the farmer's market, go to the same church. Old customs and old culture do not just exit the stage, as in the case of the demolished African village. The new owners, imitating the lifestyle of the chateaus old inhabitants, repeat the external behavioral traits of those who lived here before. They copy what can be copied, that is, what they see. Yet the culture that gave birth to this rhythm and this way of life is left outside of their visions scope. Of course, it isn't just the case of the snappy Muscovite who decided to sell the family estate: In a neighboring chateau, a group of tourists who came by bus are lead down a corridor by the young heir's black girlfriend. Explaining what her ancestors did here and there, she points to the portraits which have no connection to her. "This is my grandfather, the general," she says, nodding at a portrait of a haughty-looking white gentleman, although earlier in the day, while quarreling with her boyfriend, she threw a soft-boiled egg at it. The absurdity of the situation is augmented by the fact that she explains all of this to Japanese tourists, who snap their cameras and follow their guide's directions in an orderly, obedient manner, without a trace of doubt — or of interest. They assimilate, gather information, fit in. Another chateau houses a community of Hare Krishnas, who sing their hymns, dancing on the lawn. Here and there, another vehicle appears: a certain lady is buying up antique furniture.

At the same moment that the deed for the chateau is being drawn up,

the news on TV announces an explosion on a train in which several of

the film's characters lose their lives. What's at issue is not the

tour guide or the snappy Muscovite. Ioseliani does not blame them.

He blames no one. He tells a story. The old lady left the estate to

her sister; that was natural to her character and culture. And the

sister's daughter did what was natural to her character and

upbringing. The Japanese did not rob anyone, but patiently waited,

purchased the place in an honest fashion, and even use bicycles

instead of Hondas and Toyotas to go to the market, to church, and to

the bakery to buy French baguettes.

FOOTNOTES AND REFERENCES

|