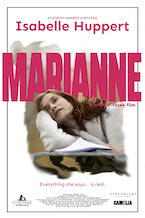

Dr. Trond S. TrondsenBeyond the Mediocrity: Marianne and the Erosion of Modern CinemaTarkovsky for me is the greatest, the one who invented a new language, true to the nature of film, as it captures life as a reflection, life as a dream. — Ingmar Bergman I recently had the opportunity to watch Michael Rozek's film Marianne – the first one-woman screen project for the exceptional Isabelle Huppert. In a stunning display of cinematic artistry, Huppert holds the camera's gaze for a continuous 90 minutes, a stretch that, for the captive viewer, feels like a brief but intensely engaging nine minutes. The film is exquisitely shot by Céline Bozon, a regular collaborator with Huppert (e.g., Tip Top, Mrs. Hyde, Sidonie in Japan). In the film, Ms. Huppert, portraying an unnamed woman, sits down and – breaking the fourth wall – speaks of her wish not to distance herself from you, but to draw nearer, to dissolve the boundary separating you from her, to genuinely encounter one another as equals. This is a remarkable example of how, at its most profound, cinema can transcend the screen, dissolving into lived experience. We forget that we are 'watching', that we are bound to a seat, that there is a screen at all. Indeed, the best films evoke something deeper than the screen – a sense of timelessness, an opening to deeper truths about our own lives. In those moments, the screen is not a hindrance but a bridge. It dissolves as we are pulled inward, into the soul of the film, which mirrors us. Today's cinema, driven as it is by the imperatives of profit and market trends, seems increasingly obsessed with plot, with spectacle, and with superficiality. This approach has led to a great impoverishment of the medium's potential. Film, at its most profound, should be a reflection on the essence of life itself, an exploration of the human soul, rather than a mere product to be consumed and discarded. It is a profound misunderstanding to believe that people are content with such superficial fare. The truth is, audiences are far more perceptive and intelligent than the industry often assumes. They crave something deeper, something that speaks to the complexity of their own experiences and emotions in an increasingly chaotic world. Consider John Cassavetes' Husbands (1970). In this film, Cassavetes ventures into the very heart of human existence, embracing its contradictions and complexities. Here, we find a stark contrast to the manufactured narratives of today's commercial cinema. His work does not cater to facile resolutions or neatly packaged stories. Instead, it delves into the raw, unfiltered aspects of life, capturing the tumult of human relationships and the existential struggles of its characters. In much the same way, Rozek's approach aligns with the true spirit of cinema as an art form that seeks to uncover deeper truths about our existence. The film is driven by his genuine desire to understand and portray the intricacies of life – Life itself. In Marianne, we witness a courageous exploration of the human condition, a reminder of what cinema can be when it dares to engage with the real, often uncomfortable, dimensions of our lives. This is, I believe, what people truly yearn for, and it is what cinema should strive to deliver. Film should capture the real essence of life, and Marianne embodies this ethos perfectly, offering a refreshingly authentic experience. It exists in its pure form, as an experience, a presence. It is simply there, in its being.

Marianne is still – shockingly – without distribution and actively seeking it (2024). Hopefully, the film industry will recognize the audience's appetite for something so refreshing, wonderful, and powerful, and take steps to rectify the film's situation – to their own advantage. |