|

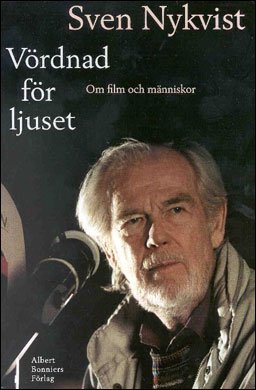

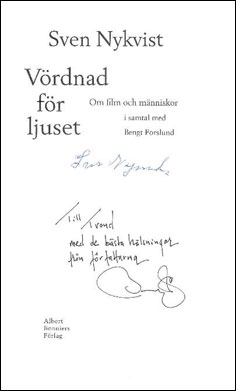

Sven NykvistOn the Shooting of The SacrificeSource: "Vördnad för ljuset" (In Reverence of Light), by Sven Nykvist and Bengt Forslund. Albert Bonniers Publishing Company, ISBN 91-0-056316-1, © Nykvist/Forslund 1997. The following comprises pages 181–188 of the book (excluding all photographs), taken from the the chapter "From Tarkovskij to Woody Allen." This excerpt translated from Swedish by Trond S Trondsen of Nostalghia.com. It is translated and published here with the kind permission of the authors. A Japanese (re-)translation is provided by Kimitoshi Sato of Japan. The photo below is taken by Lars-Olof Löthwall, and is used with his permission.

But, those of us who are freelance and rather independent often do not think along those lines. Creativity surely doesn't cease at a certain age. Many artists, composers, authors, and filmmakers are still active will into their eighties - not to mention actors and actresses. The fact is that I received some of my most exciting assignments, and did some of my best movies, at an age usually associated with retirement. It began with Andrej Tarkovskij's The Sacrifice, 1985, and continued the following year with Philip Kaufman's film adaptation of Milan Kundera's novel The Unbearable Lightness of Being, followed by some years of cooperation with Woody Allen. I had a great admiration for Tarkovskij (1932-1986) ever since I saw his fresco on the icon painter Andrej Rubljov. It was a true revelation to me when I saw it for the first time. Pure image magic! His exile from the Soviet Union led him, by chance, to Sweden via Italy where he in 1982 did Nostalghia with Erland Josephson in the lead role. They became good friends. Anna-Lena Wibom of the Swedish Film Institute was also one of his long-time friends. In Cannes in 1984 Tarkovskij was invited to shoot his next film in Sweden. He had several potential film candidates, but in the end the choice fell on The Sacrifice, which was written for Erland Josephson. My friendship with Erland, combined with Tarkovskij's admiration for Ingmar, resulted in me being asked if I wanted to be the cameraman. It was not a difficult choice at all, in spite of the fact that at the same time I was offered to shoot Out of Africa with Sidney Pollack. Erland and I even invested our artists' fees back into the film and thus became co-producers through our mutual corporation. It was not at all good business, but certain experiences are well worth the money, and, besides, I received a prestigious prize in Cannes for the film. From a personality point of view, I and Andrej got along very well indeed. We started out by watching each other's movies. His appreciation for Bergman, and mine of his movies, caused us to muse on the many obvious differences. I could see that he obviously was not very interested in lighting. To him, of primary importance were composition, camera movements, the literally moving image. He was not even interested in the actors. He blamed this on his shyness, combined with language difficulties. The important thing to him became choosing the correct types of people, with a particular kind of look, and to see to it that they had the right way of expressing themselves. Close-ups are also strikingly rare in Tarkovskij's movies. He preferred to see the actors' movements at a distance, almost choreographed, and alway in the center of the frame. This caused our working relationship to be somewhat strained during the first few weeks of shooting. As opposed to in the case of Ingmar, Tarkovskij had no prior knowledge whatsoever of the location of shooting until he got there and could sit at the camera and plan and direct its movements. This would often take hours. Add to this, that only when Tarkovskij had made up his mind on how he wanted things, could I come in and set the lighting. And since the shots at hand were more often that not extended tracking shots, things could take an inordinate amount of time. One must deal very carefully with what is only seemingly unchanging exterior lighting. In addition, there were the associated changes in image definition and contrast which the assistant cameraman had to learn to deal with. But when the images had finally been recorded, there were as a rule a considerable amount of minutes of exposed film in the camera. It was a different way of working and the result bears witness to the fact that one way may be as good as, or better, than another. Great artists go their own ways. And the photographers role is to yield, it is always the director's wisdom that counts - if indeed he knows what he wants. And Tarkovskij knew what he wanted. He had a scene he had dreamt about doing for a long long time, for ten years, he claimed. It was to be the final scene of The Sacrifice. The main character's house burns down to the ground before his very eyes, he apparently goes insane and is taken away in an ambulance. The entire scene was supposed to be done in one single take while the camera moves along a hundred meter long rail. We had special-effects people brought in from England as there was a requirement in place that the house burn down in eight minutes and ten seconds sharp. Otherwise the film cartridge would run out. For an entire week this scene was meticulously rehearsed. We had decided to not shoot the scene under sunlit conditions, and so we were forced to get up at two o'clock in the morning, do a few test runs, and then to commence shooting the scene at a carefully selected moment just prior to sunrise. Approximately half-way through the take, my assistant yells out, "Sven - the camera is losing speed! We got twenty..., now we're at sixteen frames per second! What shall we do?" Just to be on the safe side, in case problems should arise, I had deployed another camera approximately midway along the rail, so I said, "Swap the cameras!" Within thirty seconds he had changed the camera and we continued filming. Tarkovskij had not noticed that we had changed camera, nor had the majority of the others. They were all watching the fire, and when it was over and the ambulance had made its exit everybody cheered over the fact that everything had turned out so well. Then I got to tell about what had happened. Tarkovskij almost cried. The film was immediately developed to see if we in spite of everything could use some of the existing material. But, there was no way. Whatever the case, it was definitely not the sequence Tarkovskij had dreamt about for all these years - and it was even supposed to be the climactic sequence of the movie. We really didn't have the funds to re-build the house and to do a second take. Long discussions ensued, where even Erland and I were involved in our roles as co-producers. The actors were fortunately still under contract for another while. We received some additional funding through our Japanese co-producer, and in the end we all decided to give it another shot. Nothing is impossible, as Ingmar Bergman was fond of saying. It was his gang behind the camera here. The house was re-built! This time, however, I requested of Andrej that he agree that we build two sets of rails, and that the shoot should, just to be safe, be be shot simultaneously by the two cameras mounted at slightly different elevations. For an entire day we rehearsed with both cameras to ensure that they both moved in identical manner. We shot the scene one morning when everything seemed just right, but at the same moment Andrej was about to yell "Camera!" the sun appeared. Tarkovskij shouted, "What shall I do?" I said, "Look, there's nothing you can do,...! The sun is coming out, the house is already on fire - and we're on our second house!" Fortunately, it turned out just fantastic. As the smoke billowed forth from the house the sun shone right through it and generated some truly great shading on the ground. It was a lucky strike indeed that the sun appeared - entirely to our advantage, and Tarkovskij was exceedingly pleased when he saw the end result. While certainly a stubborn perfectionist, he was also willing to be corrected, at least by people that he trusted. It turned out, actually, that he at times was remarkably bound up by what he had once learned at the Russian film school. I recognized this exact phenomenon from my earlier cooperation with Barabas and Polanski, these also deeply affected by Eastern European film schools, perhaps the best schools in the world, with their much stricter set of ingrained rules than what is commonly found in the western world. At times there were purely practical reasons for such differences. For instance, Barabas and Polanski wanted to do fine tuning of color balance on-the-fly, directly in the camera, as opposed to later in the laboratory, which certainly is better and simpler, but then again the standards of quality at eastern laboratories were hardly the same as in the west. In this case they did yield to my suggestions. They seem to have been taught that tracking shots should be employed as frequently as possible - I have rarely done as many tracking shots as I did with these three directors - shots which do indeed hold undeniable cinematic value. But in the case of Tarkovskij, the school had taken it so far as to even forbid the use of such a practical tool as the oblique pan. One of the first images we were to shoot for The Sacrifice was such a shot. We were to pan across from a close-up on a glass of water and then up on Erland Josephson who was sitting at a distance away. Tarkovskij vehemently insisted on first tracking horizontally along the tabletop and subsequently vertically up to Erland, which of course took a much longer time than if we went at an angle up from the glass of water and right on to Erland's face. Only when he saw the alternate take did he admit that this was indeed the better approach. As a rule, however, it was Tarkovskij's own visions that counted even if he at times had a hard time communicating them, partly due to the language barrier - he had to constantly work through an interpreter - but primarily due to the fact that he first and foremost wanted to communicate emotions, moods, atmosphere. By images, not by words. He wanted to impart a soul to objects and nature. Here he actually went further than Bergman ever did. Once I understood this, it became a true delight to work with him and we ended up becoming very close friends. He also saw how my lighting had the effect of amplifying his own vision. I remember, among other things, how well we worked together when we after the shooting was completed performed the, to the movie so significant, color reduction in the laboratory. In the same way Ingmar and I did in A Passion, and he himself had done in Nostalghia, we removed from certain scenes almost sixty percent of the color content. A cameraman's work is indeed not done until there is a properly lighted and approved opening-night copy. Good lighting people in a laboratory are invaluable. Nils Melander of Film Teknik has been my great support during all my years of working in Sweden. This my work on the color reduction on The Sacrifice eventually caused me to meet one of my big director heroes, namely the Japanese Akiro Kurosawa. There were at one time serious plans that he, Fellini, and Ingmar Bergman were to do a period movie together. Ingmar and Fellini met in Rome, but Kurosawa never showed up and in the end the movie never materialized. Some years after The Sacrifice had been released I received an offer to shoot an industry commercial film in Japan. I had not previously had the opportunity to work there, the job was well-paid, and I saw the opportunity of perhaps running into Kurosawa. So, I took the job. I am unfortunately a rather shy person, one who does not usually initiate making contact, so when my assignment was all but finished two weeks later, it looked like I would be going home without having met Kurosawa. But, once again, I was in luck. Kurosawa was at that time close to eighty years old (b. 1910) and was about to receive some prestigious national achievement award. A large party was being thrown in his honor. The organizing committee, which had taken notice of the fact that I was in town, actually invited me. The Sacrifice had, as you know, been a Japanese co-production and the picture had been the object of much attention when it was first screened in Tokyo, which was only shortly prior to my visit. Kurosawa had seen the movie - and lo' and behold suddenly he was the one interested in meeting me! He absolutely wanted to know how we had managed to work out the color reduction. As soon as we had been introduced to each other he pulled me off into a separate room where we could sit undisturbed during the dinner and discuss color reduction processes. One never forgets such an evening. I also asked him why he never showed up in Rome. "I was too shy," he said, "Bergman and Fellini are way too big for me."

|

|