James MacgillivrayAndrei Tarkovsky's Madonna del Parto

James Macgillivray is from Toronto. He is currently (2003) finishing his Masters in Architecture at Harvard Design School.

This paper first appeared in the Canadian Journal of Film

Studies/Revue canadienne d'études cinématographiques, Volume 11, Number 2 (Fall 2002), and

is reproduced here with the kind permission of the author and of CJFS.

The author wishes to thank Alessandra Ponte, Georges Teyssot and P. Adams Sitney.

Gorchakov's exile, like Tarkovsky's, is expressed and manifested in a project: the purpose of his trip to Italy is to research the life of Pavel Sosnovsky, an 18th century serf composer whose nostalgia for Russia in Italy drives him to suicide. Sosnovsky's story within the film is a mirror in which Gorchakov can better perceive his own nostalgia. Tarkovsky, in turn, can be said to "work through" his own nostalgia by interrogating and manipulating the character of Gorchakov. Sosnovsky is therefore the diegetic denotation of a generative structure for the work, Nostalghia (Italy, 1982, Andrei Tarkovsky). As such, Sosnovsky is an example of a narrative device known as mise en abyme, a condition in a work of art where a fragment of the work replicates, in miniature, the entire composition of the work. The mise en abyme of Nostalghia is unique because the symmetry across scales (a story within a story) ultimately points back to Tarkovsky. The making of Nostalghia, the nostalgia of Tarkovsky himself, is contained within Nostalghia. In Sculpting and Time, he says that "the camera was obeying first and foremost my inner state during filming" [3]. In this sense, the technical aspect of Nostalghia implicates Tarkovsky's inner state just as the behaviour of Gorchakov follows the imperatives of the film's production. The first scene of the film, Eugenia and Gorchakov's visit to the Madonna del Parto, exemplifies Nostalghia's ambiguous agency. Gorchakov wants to see the painting because it reminds him of his wife. Tarkovsky chooses the painting because it reminds him of his wife. Tarkovsky also chooses the painting because it is not well known and, therefore, allows him greater artistic license in using it in his film. By contrast, heavily touristed sights like the Campidoglio require a total fidelity in order to be plausible to an international audience. At Piero's fresco, however, he can and does take great liberties manipulating the painting so that it "fits" in his film. Gorchakov goes to the out of the way location for a similar reason: he dislikes tourists. Yet, the question that lies at the heart of the scene remains, why, after traveling hundreds of miles to see the Madonna does Gorchakov not enter the chapel? The answer to this question lies in the relationship between Gorchakov and Tarkovsky. This paper wishes to show that in this first scene of Nostalghia the Madonna del Parto is refracted and reflected in the mirrors of the film's mise en abyme, until it becomes something fundamentally different, both emotionally/culturally and technically. It will be shown that this scene incorporates two primary artistic manipulations of the Madonna del Parto in order to present Tarkovsky's idea of the work. The first manipulation is to move the fresco to a new architectural site and to manipulate the architecture of this new site as a decentralized field condition that brings the painting into the film. The second, and overarching manipulation is to create the ritual of the Cult of the Virgin, a new meaning for the painting itself. It is precisely the extent and breadth of these interventions that exclude Gorchakov from being present in the chapel. As the director, or what he refers to in Sculpting in Time as the "demiurge" of the film [4], Tarkovsky must have felt that his own presence in the scene was too strong to include his stand-in protagonist. Gorchakov must wait outside. The Madonna del Parto and the Capella di CimiteroIn 1979 Tarkovsky went to Italy and filmed the documentary Tempo di viaggio with his soon-to-be collaborator on Nostalghia, Tonino Guerra. It follows Tarkovsky and Guerra as they tour Italy in search of locations and make short studies of prospective sets. As such, Tempo di viaggio is emblematic of the blurring that occurs between Tarkovsky's inner state and the technical production of the Nostalghia. At this point in Tarkovsky's plans for the film, Gorchakov was to be an architect. Guerra, who was familiar with such a protagonist through his work on Antonioni's L'Avventura, seems to opt for similar sets in Nostalghia. With fervent admiration he shows Tarkovsky the Baroque architecture of Lecce and many other famous sights. Yet, Tarkovsky is not satisfied. He states, "The south shore is too beautiful, resort-like and annoying... I want to interfere with people and accidents, feelings, not beauty and architecture" [5]. Later in the film he rejects not only the architecture but also the spatial sense of Italy. He says, "Italy is a country still without the ability to understand perspective and proportions. They have no sense of depth perception. In the south of Italy, everything is on the same plane and it confuses me" [6].When he toured Italy for Tempo di viaggio Tarkovsky was searching both for sets and for information about himself, the Russian tourist. In this self-exploratory sense, Nostalghia does indeed mirror Tempo di viaggio; many of Gorchakov's words are in fact direct quotations of Tarkovsky's dialogues with Guerra. Yet Tempo di viaggio, as a stage in the technical planning of Nostalghia's artistic image, is almost wholly discarded by the director [7]; it is a negative image. Thus, while both films contain the Madonna del Parto, Tempo di viaggio is forced to show only the painting and none of its surrounding architecture. This is due to the fact that Nostalghia will recast the fresco in another church, within a totally different architecture. Tarkovsky must cover his tracks. Yet the Madonna del Parto as it existed before Tarkovsky, as it existed "in itself," is worth describing here, even if only to accentuate his moves.

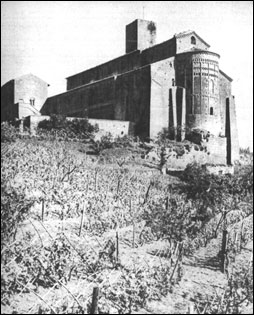

The original location of Piero della Francesca's Madonna del Parto, is the Capella di Cimitero of the Santa Maria della Momentana in the town of Monterchi near Arezzo. This church in its entirety was in existence before 1230; it was a simple Romanesque structure facing east with a circular window above the door whose interior dimensions were four meters wide by five meters high [8]. It was also quite a long building, a feature that led Thomas Martone to conclude that the circular window above the door was a kind of aperture for projecting light on the Madonna [9]. This relationship only properly exists with the church's original length, which created enough diffraction and the proper angle for an agreeable effect (Figure 1). In 1785, Monterchi took the site as a cemetery and destroyed two thirds of the nave, subsequently adding an entrance along the south end of the transept (Figure 2) [10].

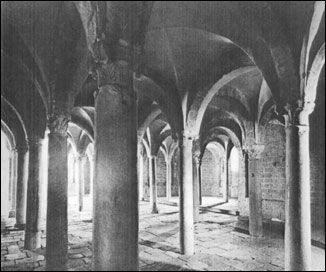

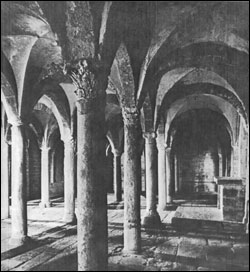

In 1979 Tarkovsky saw the fresco for the first time in the sparse, cramped space of the chapel. After the removal of the fresco in 1954 the painting would have appeared to him without a frame, resting crudely against the white walls of the East end of the church. The semi-circular top of the painting was reminiscent of the Romanesque frame but Constantino's additions and the layers of dirt would have obscured the original. What is it about the Madonna del Parto in this state that eventually inspires him to film it? On a more basic level, what does it mean to Tarkovsky to film a painting, and what aesthetic and artistic rules does Tarkovsky see at the intersection of film and art? Painting and CinemaIn Sculpting in Time, Tarkovsky advocates a complete separation between cinema and the other arts: "As it develops, the cinema will, I think, move further away, not only from literature but also from other adjacent art forms, and thus become more and more autonomous" [12]. On the dangers of not separating the cinema from the adjacent arts, Tarkovsky states, "One result is that cinema then loses something of its capacity of incarnating reality directly and by its own means, as opposed to transmuting life with the help of literature painting or theatre.... Trying to adapt the features of other art forms to the screen will always deprive the film of what is distinctively cinematic...." [13]. This quotation comes as a surprise, not only in light of Nostalghia but because Tarkovsky's works invariably represent pictorial art, full frame, in at least one scene [14]. For these works to appear in his films, they must do so in such a way as not to "deprive the film of what is distinctively cinematic."The conditions for cinematic integrity in the appearance of the Madonna become even more complex when layered with considerations of the integrity of the painted work. Paintings, have their own laws that are compromised when depicted in a film. Comune di Monterchi's desire to relocate the fresco was known by Tarkovsky at the time of filming Tempo di viaggio. "We filmed Piero della Francesca's Madonna of Childbirth in Monterchi," he says in the documentary. "No reproduction can give any idea of how beautiful it is. A cemetery on the borders of Tuscany and Umbria. When they wanted to transfer the Madonna to a museum, the local women protested and insisted on her staying" [15]. (Ultimately, however, the fresco was moved to the museum in 1992.) In his journal entry and in his conversations with Guerra in the film, Tarkovsky is clearly in agreement with the local women on the importance of keeping the work in its original site. On this subject Guerra is even more outspoken; while they look at a reproduction of the Madonna in a book, he says, "The reproduction loses a lot. In the original, the walls of the church try to engulf the painting. The dust introduces blue and white shades, especially on her stomach. I don't believe in reproductions, or translations in poetry. Art is always connected to the place in which it was created." These statements by the director and his collaborator betray a view on art and context that is strangely missing from Nostalghia. Shouldn't the Madonna del Parto be filmed in its proper setting and ritualistic context? Furthermore, the obligatory use of a reproduction in Nostalghia (itself a filmic reproduction) would seem to run counter to both Guerra's and Tarkovsky's statements. Yet in light of the fresco's history one could say that both its site and its cultural and ritualistic meaning have already been weakened if not destroyed, both by neglect and by the modern concept of art. The narrative of the Madonna's progress through time is one of constant deterioration, ending in reification. It has been removed from its ritualistic context and appropriated by the museum. The extraction of the fresco from the wall (its square shape) provides the most literal illustration of a change in the painting's use; it is as if it has been formatted for reproduction in monographs on art. When Tarkovsky came to view Piero's Madonna in 1979, most of the painting's ritualistic dimension has already been destroyed, leaving it a plastic object suitable for reproduction in film [16]. The Move to San PietroThus, when Tarkovsky returned in 1982 to film the Madonna del Parto for Nostalghia, he did not use the original in the Capella di Cimitero in Monterchi, but a reproduction installed in the crypt of a Romanesque church in Tuscania called San Pietro, some 120 kilometers away [17]. The church dates from 1093 and, as the seat of the diocese, was a thriving religious centre in the Middle Ages. The building is built largely from spolia, cannibalized remains of Roman and Etruscan architecture [18]. San Pietro's crypt was the first of what would become a Tuscan typology; the altar is not located in the apse but directly opposite, at the center of the west wall of the transept (it can be seen in Figure 7). This configuration could be due to the fact that the apse was used for baptisms. [19]. It is a relatively large space for a crypt (roughly 90 square meters), providing ample room for the camera work and other considerable spatial needs of the Madonna del Parto scene. Other unique features of this crypt are its windows, due to the dramatic change in grade between the entrance and the apse of the church (Figure 4, 5). One window is on either side of the transept, while the third is in the apse concealed behind the Madonna in Tarkovsky's film.

The crypt is perhaps the only setting in which Tarkovsky could have placed "his" Madonna del Parto. The north-south axis of the transept windows, the dark recesses of thickly columned space, the window behind the Madonna, through which the birds exit the crypt, the potential within this arched matrix for the creation of framing conditions similar to those of Piero's original fresco—all of these elements create a spatial dimension which he manipulates in order to "cinematize" the fresco. The structural tectonic system of the crypt replicates the compositional structure of the fresco's original conditions. Furthermore, the structure of the crypt is within the "structure" of suture, the structure of editing. This "suture of the Madonna" is therefore a backdrop but also a structure "inside" the film itself. Tarkovsky's manipulation of the architecture of the crypt makes it contain the meaning of the scene.

Suture, Time and the Explosion of SpaceIn their definitive book, The Films of Andrei Tarkovsky: A Visual Fugue, Vida T. Johnson and Graham Petrie include a summary of this scene, which is worth quoting here because it is typical of most viewers' impressions [20]:Eugenia is seen in the pillared and candlelit interior of a church with women in black dresses kneeling in prayer in the background... In a conversation with the elderly sacristan she is politely reproached for lacking faith and is told that a woman is meant to have and raise children, in a spirit of patience and sacrifice. Meanwhile the women have carried a life-size statue of the Virgin through the church and are praying before it; Piero della Francesca's Madonna of Childbirth is visible on the wall behind them. As a woman opens the statue's robes, a flock of small birds streams out. A series of virtual match-cuts takes us from a close-up of Eugenia's face to a slow track in to Piero's Madonna and then, in black and white, to Andrei....In their summary of the scene, Johnson and Petrie delineate the two parts of the action: first Eugenia and the sacristan, then the statue of the virgin and the birds. Their use of the word "meanwhile" to link the two elements as simultaneous agrees with what most people believe they see in the scene. In fact the two elements are not simultaneous in shooting and cannot be since they occur in the same part of the crypt and do not include each other. The fact that viewers see the two elements as simultaneous reveals a fascinating difference between the experience of space and time in cinema and in architecture. An architectural analysis reveals not only this striking difference between cinema and architecture but also the brilliant ways in which Tarkovsky uses the cinema to explode architectural space. Although Tarkovsky's art is at work in all the shot exchanges of the scene, it will suffice to show the two most important sequences. These will reference the plan of the crypt (Figure 8).

The first sequence takes place over the first three shots [21]. The first shot begins with Eugenia moving towards point a from the south-west entrance of the crypt on what will be called line A. The camera begins at point w and ends at point x on what will be called track 1. As Eugenia makes her way to point a, the camera comes around for the final framing image along the transept axis. In the final frame of the shot, Eugenia at point a is perfectly framed under the arch looking straight into the camera at point x (Figure 9). Her intent gaze towards the camera imbues the coming shot exchange with the convention of suture, in this case shot-countershot. When she looks directly at the camera and Tarkovsky cuts to the next shot, the viewer expects to see what she is seeing, in other words to cut to a 180 degree change in view. However the next shot is not of the north transept but instead looks east from point a at the apse which was located 90 degrees directly to Eugenia's right (Figure 10). In this shot exchange Tarkovsky has essentially used suture to relocate the apse in the northern end of the transept. The next shot is a sidelong shot of Eugenia at point b taken from point y as she looks into the apse, reinforcing our perception that in the first shot she was in fact looking at the apse (Figure 11). Over the course of these three shots Tarkovsky has exploded the architectural space by using a 90 degree distortion of suture, thus creating a second apse. This is not a literal creation of a second apse. After all, the viewer does not come to the conclusion watching the film that this is a crypt with two apses. Nevertheless, the spatial slack created by the suture and the change in the viewer's orientation allows for the physical impossibility of the fourth shot. The importance of this spatial slack lies in the fact that the next shot shows the Cult of the Virgin proceeding to the very space in which Eugenia and the sacristan stand (Figure 12).

The second sequence is that of the sixth and seventh shot in the scene [22]. The sixth follows a shot showing the young woman kneeling before the statue (Figure 13). It resumes the third shot in which Eugenia was seen at point b from the camera position at point y (Figure 14). Recall that during shots four and five, the space in which we see Eugenia was full of the procession of the Cult of the Virgin. Yet throughout this shot which eventually tracks from point y to point z there are no candles, no women and no statue of the Virgin. During the shot, the sacristan moves into the frame at point e and continues walking until he reaches point f. The camera keeps him in the frame the whole time by tracking from point y to point z, coming to a rest at z for the remainder of the shot. In this stationary part of the shot Eugenia re-enters the frame and proceeds from point f to point g. The sacristan follows her until he arrives at point d where he stops and emphatically looks east (Figure 15). Once again, because of the sacristan's emphatic gaze, the convention of suture imbues the following shot with an expectation of the sacristan's point of view. If the viewer is aware of the simple track that the camera has followed, then the point of view shot should contain the empty apse where Eugenia was at the beginning of shot six. The next shot is filmed from the sacristan's point of view at point d, but it is not an empty apse; it now appears filled with the Cult of the Virgin, resuming the footage of shot five which showed the woman and the sculpture sidelong in front of the background of the Madonna del Parto (Figure 16). How is it then that, by the time the shot cuts, the viewer has forgotten the empty apse at the beginning of the shot? The answer lies in the fact that this shot is the longest one in the scene (2:08 minutes compared to the average of 0:32). Tarkovsky knew that the combined effects of the shot's length, camera movement and the confusing architecture of the crypt, were enough to disorient the viewer into thinking that the sacristan's point of view had arrived at an entirely different point.

Usually, in church architecture, a grid of columns reinforces one's orientation in space relative to the Eastern direction. In Tarkovsky's hands however this grid becomes like a dark wood, confusing the viewer to such an extent that we don't even recognize the apse for what it is when it is in plain view. In the criticism available on Tarkovsky and in his own writings, montage and editing are aspects of his art which are under-represented due to the emphasis on his long duration shots. His ingeniousness in this respect is strikingly present, however, when unlocked by mapping the scene in plan. The differences between the architecture in the plan and in the film reveal that not only was Tarkovsky manipulating the Madonna but was also drastically altering the crypt of San Pietro, creating another crypt. In opposition to a film that would make architecture legible (i.e., one that would explain the architectural object "as it is"), Tarkovsky gives us a totally synthetic suture of architectural space. The architecture of the crypt after Tarkovsky must be understood as a field condition; the actual layout of the space is of very little importance. What were once absolutes in the architecture (the apse, the altar, the east) become relative conditions depending upon the contingencies of the camera's field of view. The field condition inherent in the architecture and the visual field of the camera coincide. The crypt is continuous and semi- differentiated, this allows for the degree of meaning that we see in Tarkovsky's treatment, but no more. For instance, the strong light that emanates from the apse differentiates the space of each shot, but this differentiation is not powerful enough to seep into the other shots in the scene. It is not powerful enough to create a legible architectural space, only a cinematic one. The Cult of the VirginTarkovsky's mother died on the fifth of October, 1979, after he had returned to Russia following the filming of Tempo di viaggio [23]. Tarkovsky admits to the idiosyncrasy of gender essentialism mainly in relation to his mother. In Mirror (Russia, 1974, Andrei Tarkovsky), for example, when his ex-wife accuses him of being self-centered, the autobiographical character Alexei says, "I can't help it. I was raised by women." In light of this statement and many like it, the dedication of Nostalghia to his mother is a reference to the ground for his gender-essentialist and anti-feminist film. However, the words that appear on the screen at the end of Nostalghia, "Dedicato a la memoria di mia madre," are both a dedication to Tarkovsky's mother and also a return to the first scene of the Madonna del Parto. It echoes the reason that inspired Piero to paint the Madonna del Parto in his mother's native village of Monterchi. Her death in November of 1459 is believed to be the catalyst for the fresco [24]. Yet we shall see that Tarkovsky drastically changes the meaning of the painting itself by a process of ritualization and fetishization.The fresco is an extremely rare work in that it shows the Madonna visibly pregnant. It is one of the only examples, other than vernacular works, of this subject [25]. The difference in scale between the Madonna and the angels points to it being a devotional image, in practice a comforting one for pregnant women. Quattrocento theology held that the Virgin had an incredibly easy birth. St. Bernard's Legenda Aurea was still in wide circulation in Piero's time. It declared that, "She alone conceived her son without sin and bore him without heaviness, and gave birth to him without pain" [26]. The projected desire for the alleviation of pain after conception has been most likely a devotional power of the fresco since it was first painted [27]. In an earlier version of his script, Tarkovsky's invented ritual was to have been similar to the fresco's use in the quattrocento. In May of 1980, he described the ceremony as having occurred after conception: "The pregnant women come crowding here like witches, to ask the Madonna to ensure them a safe delivery" [28]. Ultimately however, the final scene necessitates a departure from both this early version and its origins. Tarkovsky's idea of the ritual may have changed due to the fact that it is called upon to criticize feminism as one of the Western tenets to which he objected during his years of exile. Utilitarian notions of freedom and the pursuit of happiness are bound up in Eugenia's character and it is on her shoulders that the full weight of Tarkovsky's judgment rests. In the modern age of safe and anesthetic births, a fertility ritual that recognizes the connection of pregnancy to mortal risk and suffering is perhaps the only way that Tarkovsky can polemicize his anti-feminist agenda. Thus the spoken element of the ritual which overlays its meaning upon the image of the Madonna's expression is orchestrated as an indictment both of feminism and of the West as a whole. Perhaps the most impressive aspect of the scene, however, is that Tarkovsky's attack on Eugenia's feminism doesn't rest upon the pious example of the other women or the argument of the sacristan. After all, Eugenia does not leave the Madonna del Parto vanquished. Her exchange with the sacristan ends in her favour and her feminism remains largely unchallenged. Yet, once she has proven her intelligence and freedom in this scene, the rest of the film records her humiliation by placing her in a sexual situation where she has no power. What Eugenia never realizes is that her humiliation in the sexual pursuit of Gorchakov is predicated upon the basic erotic condition that is set up in the first scene and reinforced throughout the film. Tarkovsky's concept of male/female polarity is stated succinctly in his journal: "What is a woman's driving force? Submission, humiliation in the name of love. And a man's? Creation" [29]. Creation for Tarkovsky is always artistic. Furthermore, artistic creation is visualized in terms of procreation and conception. In Sculpting in Time he writes, "It is like childbirth ... The poet has nothing to be proud of: he is not master of the situation, but a servant" [30]. Note that in this instance, not only is the creative force associated with childbirth but also with the female trait of submission. Thus within Tarkovsky's concept of male artistic creation, we find aspects that are similar to those of pregnancy and childbirth: the work matures as a child does, and the artist during the process of creation experiences the same humility and submission that the woman does in miraculous, selfless love for the man. The difference, however, is that the source of inception in the artist is not a man, as with women, but similar to the Virgin Mary, it is God. His "child" is a result of God's calling the same way that Mary's is a Virgin Birth. Real childbirth does not have this origin, but Tarkovsky's use of the Madonna del Parto in the opening scene and his subsequent equation of Gorchakov's wife with the Madonna sets up the circumstances needed for a fetishization of her natural pregnancy. The ultimate power of the Madonna del Parto image and one of the reasons that Tarkovsky chooses it, is that it exploits the possibility for a fetishization of pregnancy; the Virgin Birth makes the transition into the fetish by becoming visible. The visible manifestation of the creation facilitates the projection of the male phallus onto the female body. The Freudian notion of the fetish is striking in this instance by its association with the miraculous power of the Virgin. The implications of this fetish for the rest of the film are shattering in regard to Eugenia. Throughout, the correlation between the Madonna and Gorchakov's wife are exhaustively sexualized. Gorchakov's remark to Domenico that his wife is like the Madonna del Parto "ma piu nera," goes without saying. Furthermore, Tarkovsky's treatment of Eugenia's costume resonates as the unsettling frustration of the pregnancy fetish. Throughout the film, until the final scene where she has submitted to Vittorio, Eugenia is seen wearing voluptuous, loose clothing; these clothes connote sensuality to the viewer but to Gorchakov they simply underline the void of her belly. In this sense, the film sustains a dramatic irony whereby Eugenia, oblivious to the implications of her encounter with the Madonna and unaware of Gorchakov's dreams of his pregnant wife, remains mystified by Gorchakov's frigidity. This dramatic irony reaches its height when Eugenia mistakenly offers Gorchakov her breast and asks "Is this what you want?" A sexual encounter without conception is simply not within Gorchakov's erotic imagination. Through this reading provided by Freud's notion of the fetish, the romantic non-event of Nostalghia becomes intelligible.

Tarkovsky's appropriation of the Madonna del Parto within the sexual dimension of his

film should therefore be understood as a radical adaptation of the painting's meaning. The

Madonna finds itself, as it were, between the mirrors of Tarkovsky and Gorchakov. The

nostalgia of the tourist and the relentless self-exploratory drive of Tarkovsky's artistic process

darken the fresco behind a veil of projected meanings; it appears en abyme. References and Footnotes[1] Alberto Crespi. Tempo di viaggio: Interview with Tonino Guerra, RAI — Radiotelevisione Italiana, 1995: 2.[2] Tony Mitchell, "Andrei Tarkovsky and Nostalghia," Film Criticism 8, no. 3 (1984), 5. [3] Andrei Tarkovsky, Sculpting in Time: Reflections on the Cinema, trans. Kitty Hunter-Blair (Austin: University of Texas Press, 1986), 204. [4] Ibid., p. 117. [5] Tempo di viaggio (Italy RAI TV, 1979, Andrei Tarkovsky). [6] Ibid. [7] Only two of the sets in the film are kept, the "Russian field" in the first shot and Bagno Vignoni. [8] Ronald Lightbrown, Piero della Francesca. (New York: Abbeville Press Publishers, 1993), 188. [9] Thomas Martone, in Convegno Internazionale sulla "Madonna del Parto" di Piero della Francesca. Comune di Monterchi (Monterchi, AR: Biblioteca Communale di Monterchi, 1982), 13-51. [10] Lightbrown, 188. [11] Guido Botticelli, Giuseppe Centauro, Anna Maria Maetzke. Il restauro della Madonna del Parto di Piero della Francesca. Comune di Monterchi (Poggibonsi: Lalli Editore, 1994), 9-35. [12] Tarkovsky, Sculpting, 22. [13] Ibid., p. 22. [14] The most extreme example of this occurred in Tarkovsky's 1983 production of Mussorgsky's Boris Godunov at the Royal Opera House in Covent Gardens. In one scene Tarkovsky rendered the Trinity of Andrei Rublyev in a tableaux vivant, suspended above the stage. [15] Andrei Tarkovsky, Time Within Time: The Diaries 1970-1986. trans. Kitty Hunter-Blair (London: Faber and Faber, 1991), 196-197. [16] Tarkovsky and Guerra's opinions on art run parallel to the concerns of Walter Benjamin's article "The Work of Art in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction." My interpretation of Tarkovsky's artistic practices in the scene draws heavily on this article as a precedent. [17] This assertion rests on my own research. Through a comparison of the photographs and plan of San Pietro's crypt with the one that appears in the film, I believe to have conclusively identified the set of the Madonna del Parto scene. [18] Enrico Parlato and Serena Romano. Italia Romanica: Roma e il Lazio. vol. 13 (Milan: Jaca Book, 1992), 204-230. [19] Ibid., 208. [20] Vida T. Johnson and Graham Petrie, The Films of Andrei Tarkovsky: A Visual Fugue. (Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1994), 284. [21] These are shots two, three and four of the film proper. [22] Seventh and eighth in the film proper. [23] Tarkovsky's journal entry for 8 October, 1979, reads in part: "Mama's funeral... Now I feel quite defenseless. And no one in the world is ever going to love me as she did." (Time Within Time, 207-209). [24] Lightbrown, 185. [25] Ibid., 193. [26] Ibid., 193, quoting Giovanni Crisostomo Trombelli. Mariae Sanctissimae Vita, ac gesta, cultusque illi adhibitus. 6 vols. (Bologna: Dalla Volpe, 1761-1762), vol. 2, 305. [27] Ibid., 193. [28] Tarkovsky, Time Within Time, 245. [29] Ibid., 89. [30] Tarkovsky, Sculpting, 43. Figure Credits1–2: Martone, Thomas. Convegno Internazionale sulla "Madonna del Parto" di Piero della Francesca. Commune di Monterchi (Monterchi, AR: Biblioteca Communale di Monterchi, 1982)3: Botticelli, Guido; Centauro, Giusseppe; Maetzke, Anna Maria. Il restauro della Madonna del Parto di Piero della Francesca. Commune di Monterchi (Poggibonsi: Lalli Editore, 1994) 4, 7: Serra, Joselita Raspi. Tuscania: Cultura ed espressione artistica di un centro medioevale (Venice: Edizione Rai, 1971) 5–6, 8: Parlato, Enrico and Romano, Serena. Italia Romanica: Roma e il Lazio vol. 13 (Milan: Jaca Book, 1992) 9–16: Nostalghia (Italy, 1983, Andrei Tarkovsky) |