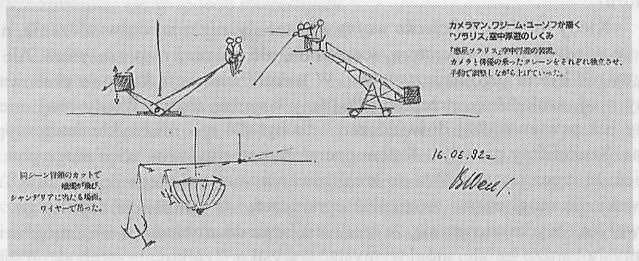

Hiroshi Takahashi in conversation with Vadim YusovTo Understand the Essence of CreationVadim Yusov speaks about his work with Tarkovsky in this interview which was published in 1992 in Japan. A Polish translation appeared in Kwartalnik filmowy (Film Quarterly) in 1995 in a special Tarkovsky issue (320 pages). English retranslation by Nostalghia.com. How did you meet Andrei Tarkovsky? We didn't know each other at school. I had already been working at the Mosfilm studio for a while when he was preparing his diploma film and asked me to work with him. He told me he had watched several films I had photographed and that he would like to work with me on the film The Steamroller and the Violin which was based upon a stage play. At that time I was just finishing my apprenticeship and was beginning to work as an independent cameraman... Tarkovsky was still a student back then... Such cases were normally unheard of in the USSR — I met with him, listened to his ideas, and I decided to do it. What was your impression of Tarkovsky during that first meeting? I can't remember the details of how he contacted me but when I saw him it was his face that struck me before anything else. He came with Andron Konchalovsky and he was very tense, he seemed a very sensitive, nervous man. He was well-dressed, elegant even, his hair was short, straight, tidy. In my opinion he had a good barber. He looked like someone conscious of what current fashion demands. His good upbringing and good manners were immediately noticeable as well, as was the ability to converse with people older than himself. You weren't much older but you already had certain experience in film... Yes, and this young man treated me as a sort of a master, advisor, or a professor. I was impressed with his tact and respect. In the end I agreed to photograph The Steamroller and the Violin. I understood it was a stroke of luck to meet someone like Tarkovsky. During my own studies at the VGIK I had no acquaintances or friends of that kind and besides, I liked his idea for the film. When did you meet him for the last time? That was in April 1983 in Milan, just before the Cannes festival. At that time he and his wife Larissa were conducting a publicity campaign for that film. I went to Milan because Solaris was being shown there as part of a retrospective. The organisers had invited me to participate in that retrospective. That was when I met Andrei. When I found out Tarkovsky was in Milan I phoned immediately and paid him a visit. It was a magnificent meeting, Tarkovsky had just extended his permit to stay, we sat until the next morning talking... He introduced me to his friends whom he invited to the Rome screening of Nostalghia but I couldn't go there as my visa was about to expire. You are one of the associates who worked with him the longest. What was the difference between your first and your last meeting with Tarkovsky? It's difficult to compare. I could say that I knew him for so long... The impressions were similar, we met as old friends. When one meets somebody for the first time one pays attention to the exterior... During my last meeting with him Tarkovsky was the same as during the first one: elegant. But the type and the quality of his clothes was different. Tarkovsky was wearing a jacket lined with fur, very expensive and elegant. I touched it, the fur was soft as silk. I said: "Andrei, this is in excellent style". His shoes were also top quality. Just by glancing at his shoes one could tell immediately this was no "man from the masses". His face changed as well but in an interesting way. So your impressions were similar? Just a moment, now I remember the jacket was lined with cashmere not fur... Over there, in Milan, I think Andrei was in some abnormal state, something odd was happening to him, he had already decided to work in the West. Larissa told me: "Vadim, we are never going back to Russia". But Tarkovsky reacted immediately: "Don't talk nonsense, control yourself". He cut short all remarks regarding his political asylum. I had a feeling he hadn't decided back then, he was still hesitating. He tried to reveal his most secret feelings, he tried but he was unable to. He understood the abnormality of the situation — we are friends but he requests the asylum. This would mean our friendship ends right then and there. The whole issue was fairly complicated. It's possible in that respect his ideas were evolving in a particular new and different direction. Unlike him I lived in the USSR, I knew the living conditions there. I told Tarkovsky what I thought about it. Our conversation has probably made it easier for him to find a solution. This is a dilemma which is very hard to understand for people in the West, also difficult to understand for the Russians today. Back then political asylum meant severing contacts with friends and family. One had to change one's life completely. People in the West could travel. They also had and still have their problems but they could travel to Italy, Japan... Our meeting was to be the last one, we felt it, this atmosphere... And so we mostly reminisced joyfully about the old times... Did he tell you anything about the film he was working on just then? Yes, of course he talked about The Sacrifice. He had great hopes for that film. One year later I was visiting Rome and I was only talking to him on the telephone. I asked for one more meeting. But it wasn't possible. He said he was very busy. I felt he was hiding his address. Then I understood he had requested political asylum. I proposed several ways to organise a meeting but it never came to be. I think Tarkovsky was afraid I was being followed by KGB agents and that they'd find him by following me and he'd be forced to return. He was afraid of that, he couldn't take that risk... Ivan's Childhood contains many "visionary" elements, the scene with the truck and the apples for example. This kind of imagery was thought of in the West as very "fresh". A new term was gaining currency: "socialist surrealism". Was this manner of film imaging proposed by you or by Tarkovsky? In those days we lived in the atmosphere of "avant-garde". We'd already seen Buñuel, Godard, and we knew Kafka. That's why this was all "in tune", this was very important. Socialist surrealism wouldn't be a good description for this film. In those days there were many experimental films made, also in commercial cinema. When we were shooting Rublov the most important film for us was Kurosawa's Seven Samurai. Tarkovsky thought very highly of this film. There are many "quotations" from Kurosawa in Rublov. Tarkovsky would always keep a list of directors he admired and liked. The ordering of the names on that list changed in the course of time but Buñuel, Godard, Kurosawa were always on top. Was Tarkovsky very demanding for the cameraman during the course of his work? When we were doing Ivan's Childhood he was young, he had no experience, he didn't know much about the role of the cameraman, the set designer, and also of the director. But I was never his teacher. During the filming of Rublov we worked together, we searched, we studied together. By then we already had certain experience — for us this was an especially interesting time. We searched for truth... I am a cameraman, a technician, thus I can say: this can be done, I can undertake this assignment. But Tarkovsky frequently could not understand the limitations and this ignorance made him bold — he thought things would be easy to do and he could have very daring ideas, he could invent anything, in total freedom. Namely, thinking up images (visions, imaginary scenes) — this is exactly how we shot. We didn't invent anything, no new film technique, but we did frequently create a kind of new expression. I am certain: at the technical level, during the photography, we've found something that was relatively new, fresh. Do you recall, for example, that scene in the forest with the officer and the woman? Tarkovsky said one had to shoot this scene from below the ground level, so I created something that could hold the camera in that position, so it photographed our hero from the interior of the earth. In those days there were no films applying this style. Today, of course, one can find such scenes. Cinema always forces a subordination to technology. Having mastered it, one can utilise technology to influence the content and expressive power of film. Also the other way around — the technology itself can modify what the artist intends to express... Of course, the relationship between the cameraman and directing is a very interesting one. This is a very personal problem for me. The work on Rublov was an unending search and trials. I must say that each of us was able to find our own truth. The shooting of this film was precisely thought through, planned in detail while still in preproduction. We were prepared well. We detailed the mutual relationships between the lengths (durations) of the dialogues and the lengths of each scene i.e., the duration of the image. And for the tracking shots — the relationship between the distance camera-object and the duration of the tracking. How did you film the library levitation scene in Solaris? We knew the American method beforehand but we had no equipment of that type. We had to find our own way to film that scene. We thought for a long time, we tried many things and in the end — I believe — it came out rather well. We didn't invent any new technique, of course. The device we used was quite simple. The effect of what was happening in that scene was kind of a miracle and it was achieved through editing effects and correctly synchronised camera movements. Simply, the camera position was changing. The most important thing was the correlation between the speed of the characters' movements and the number of scenes. We had to regulate this, set up beforehand, already at the preparatory stage. Was the camera and the actors on a crane? Yes, I'm drawing it for you now.

The device was simple. The crane with the actors is raising, the other crane, with the camera, is raising as well. But the crane with the actors covers the background decoration — we had to pay attention to this. We also noticed that if both raising motions were the same, the effect looked bland. A certain dissonance (lack of parallelism) in the movements of both cranes was necessary. But if the differences in the motions were too great, the crane would become visible. Did you move the camera yourself? Yes, after rehearsing many times. At first the crane was moved by an electric motor but that didn't produce a good effect. Beginning with The Steamroller and the Violin all the way through Solaris you worked on all films by Tarkovsky. You did not participate in realisation of The Mirror. Why didn't you want to make this film? What were your impressions from reading the screenplay A White Day, the literary basis for The Mirror? It's difficult to explain. It's true, I refused to photograph The Mirror. There were several reasons. Firstly, I worked so much and for so long mainly with Tarkovsky. When the cameraman and the director work together for too long, the cameraman can sometimes feel he is under too strong a pressure from the director, on his own territory, and this isn't good for the film. Working together on one film for a very long time is particularly detrimental to mutual relationships. Pressure and possessiveness lead to weariness. In the end one should work alone. Tarkovsky has "invaded" my territory. Obviously, I ought to understand the director's role. Film set is where discussions take place continuously, quarrels sometimes, exchanges of ideas. One ought to understand what the director wants. But when I totally agree with him, if I agree with his demands I gradually become his slave. It's a psychological problem. A lot depends on the type of the scene being shot. In some cases the cameraman has the power to influence the director. Yet sometimes he is only someone like a salaried employee. I wanted very much to work on equal footing, to be in agreement with the director, to achieve a harmony in our relationship. A close psychological bond between the cameraman and the director is probably the most important thing in film. This relationship plays a greater role than marriage does in private life. In marriage there are always certain supreme rules which lead to psychologically normal relationships. There are always norms for equilibrium. Between the cameraman and the director there are none. When the cameraman accepts the director's will, the latter becomes closer than the cameraman's wife. I was really tired because of certain tension... Another reason to give up working on The Mirror was my lack of understanding of this screenplay's concept. Of course the screenplay and the film are two different things, but already at the level of the screenplay I saw something important there which I couldn't understand and couldn't accept. Today I feel there is a contradiction in the justification of my decision because when I later saw the film on screen, things I didn't like in the screenplay ceased to annoy me. There was a great discrepancy between the film and the screenplay. From today's perspective I can say that when I work with someone whose concepts I disagree with, I have to fight a battle that's too exhausting. On top of that the theme of the screenplay contained biographical elements from Tarkovsky's life. I felt the personal expression of the director could turn against the film and against me. I felt that during the preparatory stages Tarkovsky wanted to eliminate my ideas completely, my manner of perception, that he would want to direct only his vision. I thought that would be disadvantageous to me. And the third reason: when the production started, Tarkovsky's life underwent a profound change — the influence of his wife Larissa became too strong. In this situation Tarkovsky went along with the new family life, eliminating the influence of his old acquaintances. That's why I thought I could not do that film. Which film by Tarkovsky do you like and value most?

I cannot answer this question. For me cinema is not a solution, it is a process.

For example, while watching a film I am satisfied with only certain portion of it,

and the degree of this satisfaction varies. Before I begin evaluating artistic

merits I check whether the craftsmanship is good, I evaluate as a cameraman. Before

anything else I feel responsible for the photography. I cannot sleep while the

film is being processed in the lab. It's difficult for me to say which of Tarkovsky's

films I like most. Those, however, which I photographed are a unique experience

of my life. While studying at the VGIK I only had an illusion of taking part in

artistic creation. Thanks to his films I became a real cameraman and I understood

what true creation was. Interview with Hiroshi Takahashi in The Superior Ritz Cinema Autumn-Winter 1992, pp. 112–115 [Pol. trans. Ewa Misiewicz, published as Zrozumiec istote tworzenia in Kwartalnik filmowy, Spring-Summer 1995 (9-10), pp. 239–244. English retranslation by Jan at Nostalghia.com. |